- Home

- Sergio Vila-Sanjuán

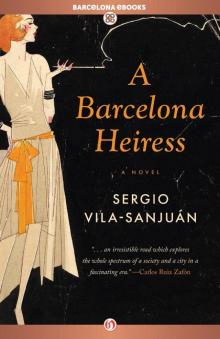

A Barcelona Heiress Page 3

A Barcelona Heiress Read online

Page 3

“I was wrong about the confrontation coming … it’s already here,” the anarchist whispered. Though he was dabbing sweat from his forehead with a handkerchief, he seemed reasonably calm.

“How did you know they were going to shoot?”

“I’m a lawyer. I spend my days at trials, and I know how killers work,” I responded curtly. The truth was I had reacted instinctively when I sensed that the two men were about to do something dangerous.

My arms were trembling. I grabbed the bottle of cognac from the waiter and took a long swig. It tasted awful.

2

As I made my way through the teeming halls of The Ritz at the party that had attracted Barcelona’s crème de la crème and was held in honor of two infantes—a Spanish prince and princess, I sensed that I would see her soon. She somehow managed to emanate a special light which bathed everything around her, one that radiated from inside rather than merely reflecting like the crystal chandeliers hanging from the ceiling that evening. This and her vivacious laugh, which enveloped the conversation around her with all the subtlety of an earthquake, made her hard to miss. And there she was.

* * *

Barcelona: a violent and seductive city, a city of passions stained with blood … Although born in the south, in the silver city of Cádiz, that Andalusian Venice surrounded by water, I was brought to Barcelona at a tender age because my father, a captain in the Merchant Navy and an officer with the passenger ocean line Compañía Transatlántica, had been named the supervisor of the city’s important Mediterranean port. I have always loved this industrious capital, brimming with vestiges of a glorious medieval past, and considered it my own. On the occasion of the 1888 World’s Fair, Barcelona had succeeded, like no other city in Spain, in harnessing the energy of the nineteenth century to modernize and endow itself with a series of urban designs and services on a par with those of the most advanced European metropolises, marking the dawn of an era of economic splendor for Catalonia.

The thriving Barcelona I knew in my childhood, adolescence, and youth, however, was plagued by a scourge so recurrent that it would come to form part of daily urban life for the city’s people: social and political violence. From the first explosive in 1886 at the Fomento del Trabajo Nacional building, which housed the organization promoting business development; to la Semana Trágica of 1909, with a death toll of more than one hundred and in which more than eighty buildings burned; to the bomb placed in the Gran Teatro del Liceo in 1893, with another twenty casualties; to the chaos unleashed by the First World War, from 1914 to 1918, no other European city was more beleaguered by anarchistic violence than Barcelona, and the successive authorities appointed by the nation’s government proved, one after the other, powerless to halt its spread.

The rapid and uncontrolled industrial development of the day brought wealth and created jobs, but along with that came job insecurity and untenable work conditions. The industrialists didn’t know how to use dialogue and social policies to appease the workers’ demands, which were at times fair, though often vented through incendiary rhetoric denouncing the fatherland, order, and religion. At the tensest of times this would result in the burning of a church or convent as, among all their supposed class enemies, the revolutionaries attacked those offering the least resistance, and didn’t dare attack barracks or police stations. The prudent and moderate movimiento catalanista, which called for Catalan autonomy, had emerged through its early political activity at the close of the nineteenth century as the sensible voice of an active and triumphant bourgeoisie committed to progress within Spain, a country which at that time found itself in a state of moral and social deterioration, demoralized by its historical decadence. Not even this movement, however, could stem the spread of violence perpetrated by the groups of trade unionists and, in order to keep these factions from frustrating many of their initiatives, they were, in fact, reduced to constantly pleading for aid and solutions from the very authorities in Madrid who they simultaneously railed against.

Catalonian industry had flourished by supplying the belligerent states engaged in the Great War, during which my mentor, the then-president, Eduardo Dato, who years before had given me my start in the legal profession in his private law firm, had pronounced Spain’s neutrality in the conflict, a decision ratified by King Alfonso XIII. At the same time the city had been flooded with German and French spies along with shady characters such as the famous Baron de König who, like so-called anarchist Joan Rull ten years before him, had been accused of such a litany of crimes committed for political reasons, on both sides of the spectrum, that nobody really knew what side he was on, that of the workers or the bosses, or if he really cared about anything at all except for lining his own pockets. In 1908 Rull would pay with his life for having deceived the Barcelona police, presenting himself as an informer and reporting attacks he himself had been behind. Meanwhile, Baron de König (a false title, of course), following his infamous exploits in Barcelona, would return to Germany where he would carry on with his mischief for many years. Like something out of G. K. Chesterton’s fascinating novel The Man Who Was Thursday, in the Catalonian capital there were many times when nobody was surprised that the anarchists were actually police, and vice versa. In the meantime, bombs exploded every day in the streets, bosses and workers were killed by the dozen, accounts of attacks carried out by anarchist groups filled the papers, and strong-arm tactics used against judges, witnesses, and defenseless citizens were the order of the day.

Against this backdrop, nihilistic and unbearable for the average person on the street, Ángel Lacalle had appeared. He was an ardent orator and a radical demagogue who saw the system as rotten, and the bourgeoisie, in collaboration with the government and the clergy, as responsible for every outrage. Without going so far as to condemn the activists, Lacalle declared himself to be opposed to personal assaults, thefts carried out by gangs, bank robberies, and the use of bombs—tactics many of his associates had no qualms about employing. This, and only this, was the reason why I had chosen to give him a few moments of my time.

Perhaps this was also why he was in the line of fire, despised by some of his fellow comrades as a tepid ally, almost a traitor to the cause, while at the same time being in the crosshairs of the police and business organizations for championing the causes of broad spectrums of the organized and militant workers movement. After a very brief lull in the violence during the final months of the World War, the triumph of the Russian Revolution had sounded warning bells around the world, announcing that overturning the system was, at last, possible. That signal had been received in Barcelona, where a devastating general strike in the winter of 1919, triggered by a drop in salaries and firings as a result of the end of the war, had paralyzed half the city, forcing the army to take to the streets to re-establish some semblance of order. The situation had become so serious in recent times that, of the four government branches in Barcelona—the City Hall, the Mancomunidad (comprised of the governments of the four Catalonian provinces), the Civil Government (which controlled the police), and the Captaincy General, which held authority over the Spanish army in Catalonia—these last two entities had come to the fore, enjoying ever-increasing levels of autonomy.

Following the strike, violence on the streets flared up and gunmen had begun to oil their Star revolvers once again. The failed attempt on Lacalle’s life in my presence at La Puñalada, whoever was behind it, attested to this. I always found it surprising how often assassins missed their targets, even when able to get very close to them. Perhaps in this case they would have been better off using knives.

The period I now describe began at the end of the First World War and ended with a change of regime, though the key and decisive events for me would occur within a matter of months.

* * *

Perhaps it can be said that in my city, despite its population of over half a million, among just a few people, on certain levels, “everyone knew each other.” What I mean to say is that, despite the aforementioned figur

e, Barcelona was also a city with a small number—thirty? forty? fifty?—of elite and intricately intertwined families who stood as the arbiters of society, set the tone for its elegant diversions, and whose whispers swayed the decisions of the politicians and military leaders in power. The lineage of several of these families stemmed nearly all the way back to the era of the Marca Hispánica, when powerful dukes and counts governed the borderlands between the Franks and the Moors, and to the Crown of Aragon. Some owed their nobility to the Habsburgs, and had resisted the temptation to relocate to Madrid, home to the Court and real power and influence. A good number boasted Bourbon titles, while others had been made nobles by Alfonso XIII himself, who had not hesitated to so distinguish those Catalonian patricians who had created great companies or patently demonstrated their loyalty to the monarchy.

Along with these nobles, among them landed gentry and the owners of large pieces of property in Barcelona itself, were financial magnates and leading captains of industry, in addition to business leaders in textiles, electricity, transport, and the press. In short, they constituted a kind of club with indeterminate boundaries in which, after a time, it was easy for one to tell, from the accent—a sibilant Castillian, or a neutral and melodic Catalan—or the manner of dress, or the location and size of one’s houses, or the education one’s children received, who belonged and who did not.

* * *

I was headed for an engagement with just this enclave a few weeks after my first meeting with María Nilo and Ángel Lacalle, both of whom I had been thinking about ever since. The singer was a singular and somewhat slippery character, while the activist had a decidedly powerful personality. I could not help but wonder about the nature of the relationship between them, and how I had suddenly become entangled in their disparate but apparently convergent paths.

An early evening breeze accompanied me as I walked down Cortes Street dressed in my tailcoat. I made my way with some difficulty through the crowd, which was flanked by pairs of mounted Guardia Civil and government security officers.

The occasion was a royal visit. At that time, the king of Spain, Alfonso XIII, did not often travel to Barcelona, in part for security reasons, and in part because, thanks to the escalating catalanismo, he hardly expected to receive the warmest of welcomes. The president of the Council of Ministers, my mentor Eduardo Dato, had shared with me that he had sought to persuade the monarch to visit more often, for it was on such short journeys when Don Alfonso really shined. He knew how to win people over, and he certainly had potential in Barcelona and Catalonia, for even there monarchical sentiment was still very much alive in many circles. But on this occasion he had dispatched the infantes Doña Luisa and Don Carlos on his behalf for the inauguration of the new Red Cross Hospital. Don Carlos de Borbón de las Dos Sicilias, Count of Caserta, had taken as his first wife the infanta María Mercedes, Alfonso XIII’s elder sister, who would die during labor delivering her third child a few years later. The monarch’s brother-in-law was thus on close terms with the king, and resided at that time in Seville as the captain general of Andalusia. His second wife, Lluisa de Orleans, was the Count of Paris’s daughter, and a charitable soul who had thrown herself into efforts to promote the Spanish Red Cross, whose first patron had been Alfonso XIII’s first wife, Victoria Eugenia de Battenberg.

In the morning their Royal Highnesses had arrived at the train stop on Paseo de Gracia, where all the city’s authorities and most prominent social figures had turned out to receive them, while a brass band struck up the Royal March. Leaving the station, they boarded the mayor’s carriage and crossed the city to the cathedral as the crowds honored the royal family with shouts of “Viva!” Security forces had scoured the entire route beforehand. After the perfunctory Te Deum and the subsequent tour of the city’s other emblematic church, La Basílica de la Merced, the infantes had headed for the Captaincy General, where their rooms had been prepared, lodgings which could hardly be called luxurious. Barcelona had no royal palace to accommodate crowned heads and their relations when visiting the city ever since the building near the port, which had once welcomed noble visitors, burned to the ground in 1875. In fact, when the Queen Regent María Cristina and Alfonso XIII, then two years of age, were in the city for the 1888 World’s Fair, they had to stay at the city hall.

From the balcony of the Captaincy building, the infantes watched a parade featuring brigades of infantry regiments from Vergara, rifle battalions from Barcelona, and dragoons from Santiago, Montesa, and Numancia. In the afternoon the infantes had visited Tibidabo mountain.

I had followed them everywhere since the editor of El Noticiero Universal, Julián Pérez Carrasco, had asked me to take charge of all the information, as was often the case when monarchs or other high-ranking national leaders visited Barcelona. In addition to theater reviews, I was usually assigned feature articles rather than covering events on the street, but certain occasions merited exceptions. The paper’s management toed a conservative and decidedly pro-Alfonso line, and both my political background as a member in my youth of Las Juventudes Monárquicas and my strong contacts in Madrid inspired the owner’s trust in me. The same could not be said of some of my fellow journalists who, while capable, were definitely more left-leaning. As my practice was still just getting off the ground, it was not difficult for me to balance my different activities.

There was nothing like a royal visit to inspire and stir up social competition between Barcelona’s best families. The infantes’ evening began in the halls of The Ritz, inaugurated just months before. During the boom years of the Great War it had become all too evident that the city did not boast a hotel fine enough to welcome affluent international tourists and businesspeople, a shortcoming all the more troubling when it was officially announced that the city would host the 1923 World’s Fair (which would ultimately be postponed for a few years). A commercial attaché with the British embassy in Madrid had even informed me that when this event was held, they would have to anchor some large steamships in Barcelona’s port in order to provide accommodations for all of the international visitors, for the city’s offerings would not be sufficient. This situation spurred some local luminaries to back the construction of The Ritz. With its neoclassical style and spacious halls, it offered luxurious rooms, complete with Roman-style baths where mosaics graced the walls and floor, among other fine touches. Its inauguration in September 1919 coincided with a coordinated series of hotel strikes, which truly put a damper on things.

But such was not the case that night, when its halls were brightly lit and bustling with guests well-accustomed to donning evening wear, black ties, and gala uniforms. When Doña Luisa and Don Carlos entered the foyer, the hotel’s sextet struck up the Spanish Royal March and we guests formed two ceremonious lines in their honor, through which the infantes passed, followed by their entourage.

It was then that I saw her, dressed in a spectacular, shimmering glacé dress with small silk flowers sewn on the bodice and the skirt. She was marvelous, with her freckled face and her mane of hair a shade somewhere between blond and chestnut, so characteristic of upper-class Barcelona girls.

“It’s by Jeanne Lanvin … the dress, I mean. You’re staring. Do you like it? I thought you’d never get here. Have you taken down the names for your paper yet?” she asked me. “Stay by my side and I will dictate them to you: the Count and Countess of Caralt, the Marquess of Palmerola, the Count of Fígols, the Marquess of Alella, the Marquesses of Dos Aguas and of Santa Isabel, the Count of Güell, Mrs. Julia de Montander de Campmany, Mrs. Mercedes Morató de Peñasco, Mrs. Amalia Soler (widow of Vernis), Mrs. Frasquita Cornet de Roig y Bergadá, the Marchioness of Villamediana … Print something about them before anyone else, as they’re from the Red Cross Ladies Committee.”

“Villamediana is still about? I thought she had been invited to retire from her position.” The aged president was a venerated figure amid Barcelona’s upper echelons. She directed and controlled everything, from the annual debutant balls to the

collections for charitable efforts.

“We went on a cruise to Egypt and were tempted to leave her among the mummies, but we didn’t have the courage.”

I drew my notebook from my tailcoat pocket and began to write. I had never been able to resist following her instructions.

Isabel Enrich, the Countess of Vilalta, was a beautiful and willful heiress. Her father, the last in a long and illustrious but ruined line, had crossed the Atlantic when he was very young, determined to make a fortune. And he had done so in Puerto Rico, where he established one of the island’s largest sugar mills. Once he had achieved his objective he decided to spend five months of the year in the city of his birth, and the rest in the Caribbean. He was more than fifty years old and a bachelor when, on one of his trips bound for home, he met the comely daughter of a prosperous landowner. At first, this gentleman had not approved at all of someone his age courting his precious girl, who was his only child, but he ended up surrendering to the situation. They married and had a daughter, Isabel, who grew up pampered, but nevertheless became an attractive and energetic young woman, educated at the Colegio de Jesús-María and, as traditions dictated, she was formally presented to society at age eighteen, coming out at the customary ball. She was a girl exposed to a wealth of culture from a young age, thanks to the concerts and literary events her parents hosted at her home, the impressive library they possessed, French and English lessons imparted by able governesses, the family’s frequent travels through Europe during which they visited the great museums of the largest capital cities, and her own restlessness and curiosity about everything.

A Barcelona Heiress

A Barcelona Heiress